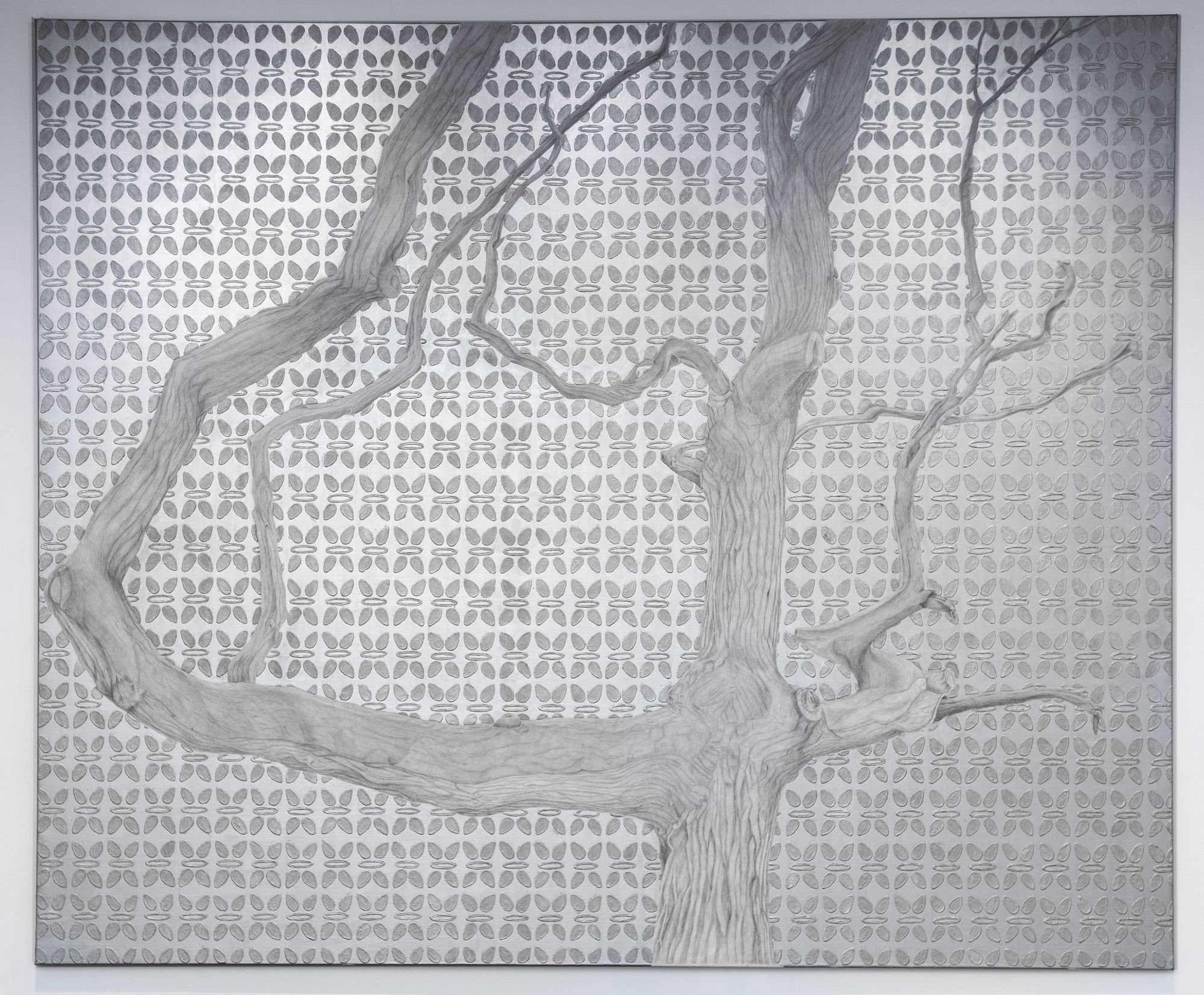

Overlapping Landscapes or Bone

In Overlapping Landscapes or Bone, Soi juxtaposes two images that together construct what he considers a vista. An oak tree whose shape inspired him and became a site he returned to often, to ruminate about his practice, is draughted against a silver pattern laid out in low relief—a reference to a blue glazed tile that sits upon a mediaeval mausoleum situated on the bank of the River Jhelum in the ancient city of Srinagar. The tree is rendered in silverpoint, a permanent medium used before the shift was made to graphite. The silverpoint oxidises gently over time, becoming warmer over the years. Over centuries, this tree will become sepia. A colour shift in the background is ignited by the pattern in low relief, painted in silver, whose reflective colouring shifts as one moves past the canvas, activating the frame and enveloping the viewer.

In Western parlance, this pattern is an “egg-and-dart” motif. It sits on the brick facade of the Tomb of the Queen Miran Zain, built by her son Zain al Abedin (1420–1470 CE), the 8th Sultan of the Shah Mir dynasty that ruled over Kashmir. This tile, unique in design and hard to pin down (it could be a lotus flower) harkens to a time when there was an accretion of Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic motifs, leading to a rich visual language in the valley and the surrounding regions, such as Ladakh, all of which would have influenced the craftsmen that constructed it.

The rich interconnections between North India and Central Asia in pre-modern times become apparent as one studies this site. Mirza Haider Dughlat, a cousin of Babur and advisor to Humayun, is also buried here, albeit separately. The four-domed architecture of the mausoleum grounds points to Central Asia; the queen Mother, Miran Zain, herself hailed from Turkmenistan.

The oak tree, situated on a lesser-travelled track in the Bergen Forest situated north of Amsterdam, is shaped by the ocean climate of the North Sea which begins where the forest ends. Its structure, in the way its branches grow vertically from its main trunk—which follows the ground before pushing skywards—reminded Soi of bone in their bare, wind-polished appearance. Its form appeared to Soi to be a composite shaped by an awkward, almost manual, attachment of branches along its trunk and became a metaphor to him of his compositional strategies, where seemingly diverse and unconnected images are juxtaposed towards the generation of a personal narrative.

For Soi these conceptual, historical, and formal strategies form a complex filigree of overlaps and intersections through which a world-view essentially becomes visible.

1

of

17