-

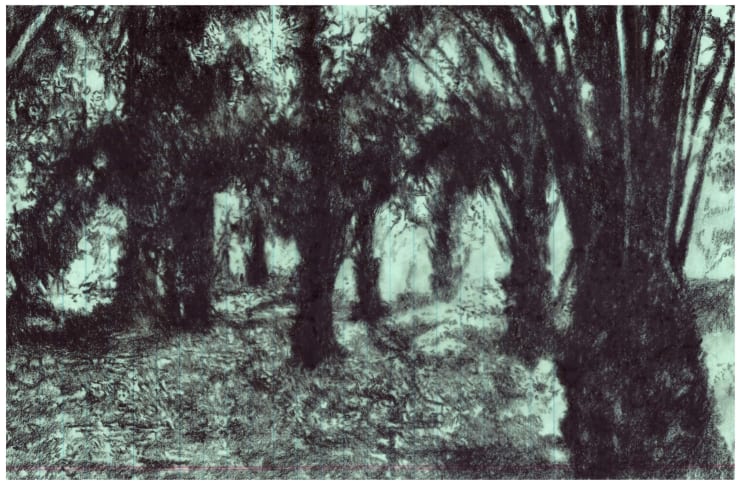

Sohrab Hura’s (b.1981; lives and works in New Delhi, India) presents oil paintings from his new body of work The Forest. The title encompasses the act of waiting within itself, evoking the forest as a space of myriad possibilities—it can harbour secrets, offer refuge, or provide a sense of solace and comfort. For Hura, the forest becomes both a physical and psychological manifestation. These works emerge from a place of remembrance, anticipation, and imagination. In the recent months, Hura has been accompanying his father to medical appointments that made him acutely aware of how time can feel interminable in the hospital waiting rooms. When he began working with oil paint, he felt a similar sense of waiting—the slow process of allowing one layer to dry before applying the next. His exploration of this new medium also stems from a desire to take a break from the heaviness of photography and his quest for tactility, softness, and meandering. While attuning himself to the physical act of making these paintings, Hura also experienced assuring affirmation of his presence in the real world.

-

For much of the past decade, Christopher Kulendran Thomas has been using advanced technologies across multiple disciplines to question the myths of Western individualism. His paintings metabolize the colonial art history that came to dominate in Sri Lanka after his family, who are Tamil, left escalating ethnic violence there. Kulendran Thomas often exhibits these paintings with video installations that fuse propaganda and counterpropaganda into a speculative vortex of alternate histories.

-

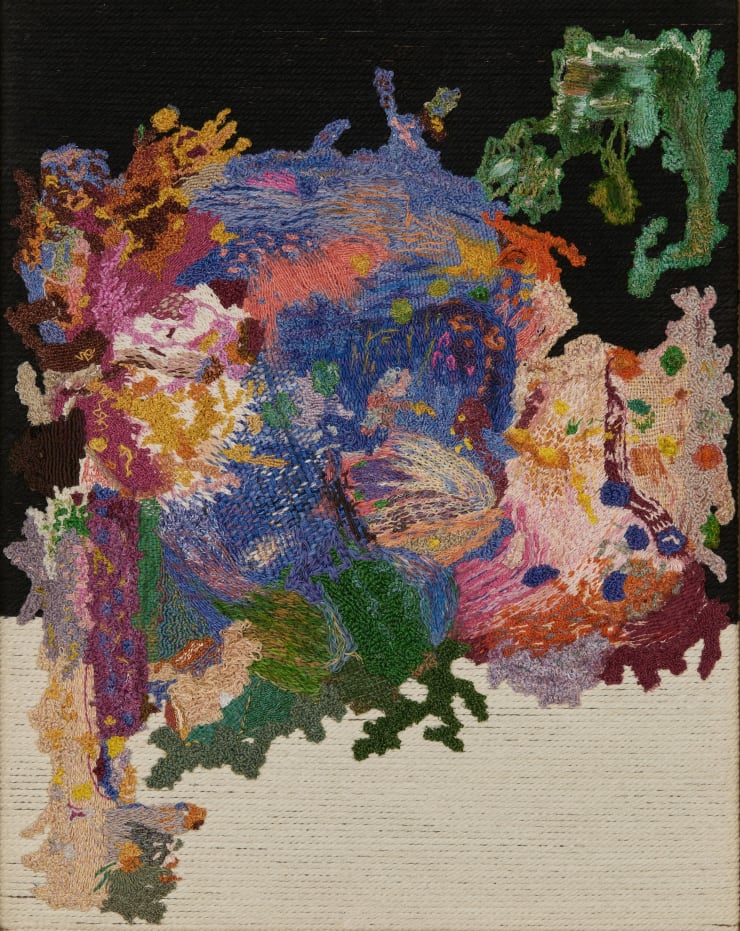

Through deep engagement with diverse indigenous textile techniques, material investigation, and inherited knowledge systems, Chanakya School’s practice, led by Karishma Swali, forms a conduit between contemporary thought and ancient processes.The works serve in equal parts an exploration of their interconnected textile histories, as it serves a repository of understanding the residues of the human hand imprinted in thread over time. Few human inventions carry our imprint across time as intimately as cloth—through cultures and centuries, textile has absorbed the personal alongside the collective, becoming a palimpsest of human experience where stories are deposited, layered, and preserved. For Chanakya School, these stories are not abstract—they carry the customs of a place, the rituals of daily life, and the social codes that shape communal identity. To trace a line of thread therefore, for the collective, is to follow an unbroken lineage of knowledge, even a physiological map or a chronological archive of our history that binds people to land, to one another, and to their communities.

-

-

-

Biraaj Dodiya

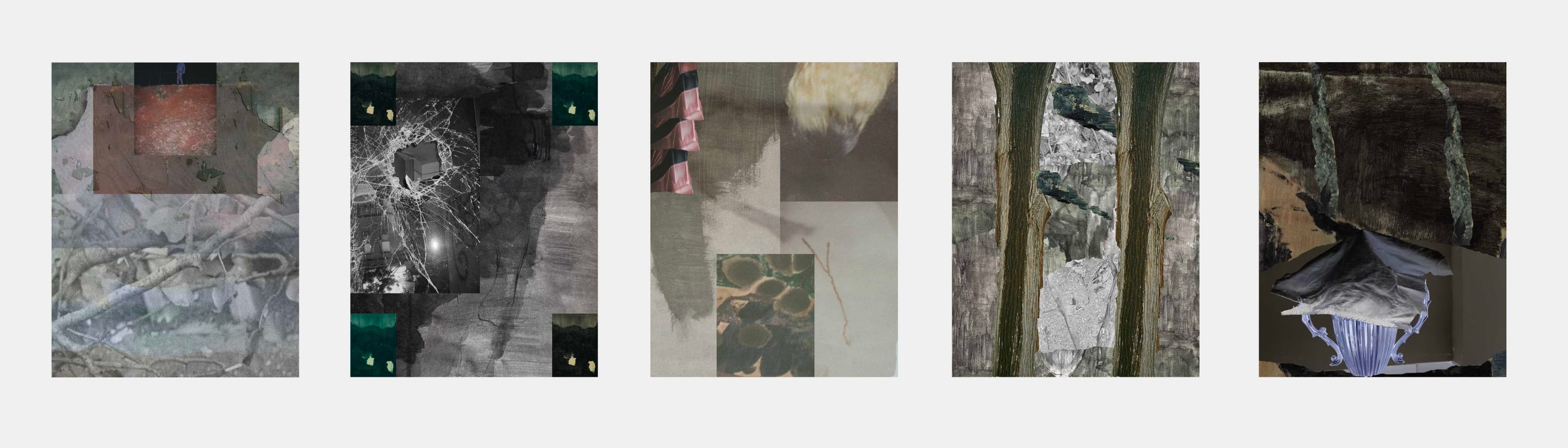

Howl, 2025-26Howl is a set of paintings in eight parts, unfolding as a single horizontal register, recalling the logic of a film strip—frames advancing, slipping, and bleeding into one another. These oil-on-panel paintings were conceived during Biraaj Dodiya’s time at the Pioneer Works, New York residency, while learning darkroom processes and experimenting with Super8 filmmaking. Interested in the meeting point between the sublime image and the inherent ruin in it, the works allude to landscape without ever settling into it. Shadow and light pulse across the sequence, images collapsing and re-forming as they shoot laterally with a quiet persistence. Ultimately, the movement feels orbital rather than linear: a passage through shifting terrain that curves back towards its beginning, like an animal’s long cry in the dark.

-

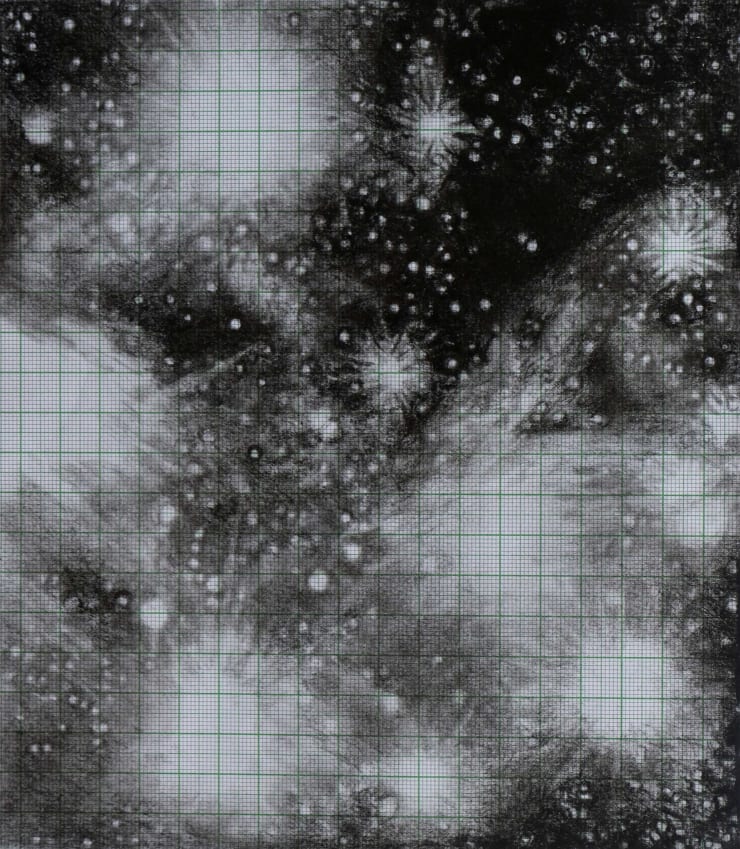

Biraaj Dodiya

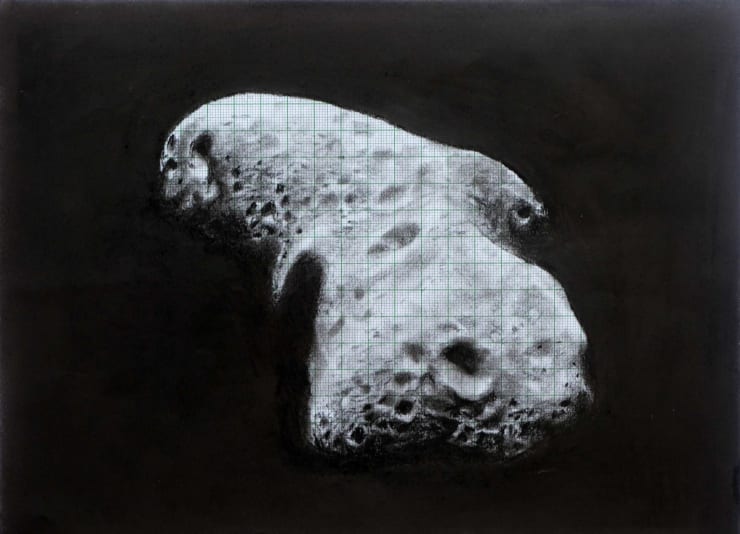

Growing Orbits, 2026Biraaj Dodiya’s Growing Orbits (2026) is a series of digital collages that combine photographic images with details from drawings and paintings. Composed and manipulated digitally, these works trace back to the beginnings of Dodiya's interest in abstraction – constructing a cryptic geography, connecting body and landscape, imagined and urban. The photographs in this particular series- from the street or from the studio, imagine scenes from a nocturnal life through forms, caverns and surfaces emerging from the dark.Images collapse and appear and visual orbits expand into possibilities of vast perimeters. Through the transparency and overlaps, the final image develops a scan or x-ray like quality, almost as if it were exposing the organs and bones of her processes.They contain diagrams, suggestions, clues, questions, spontaneous conjurings and ways of looking. Decay and formation become verbs of a poetic interchangeability; the image arrived at, is a tentative map of the world charting a choreography for searching. -

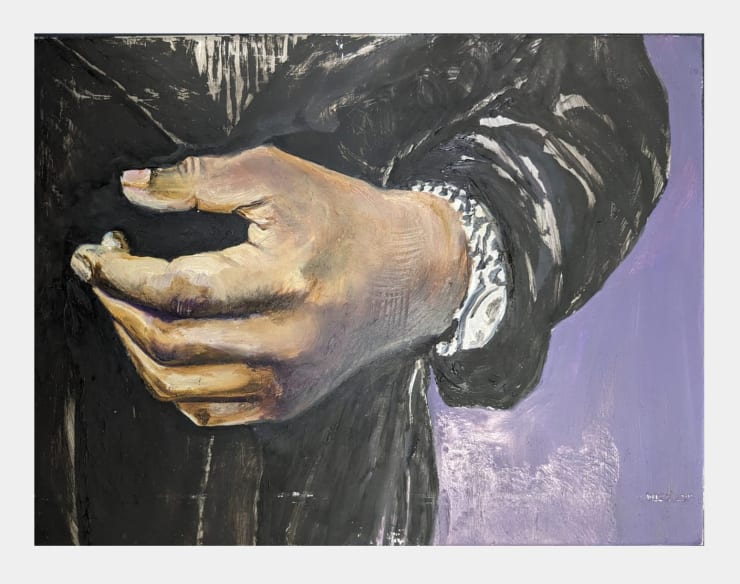

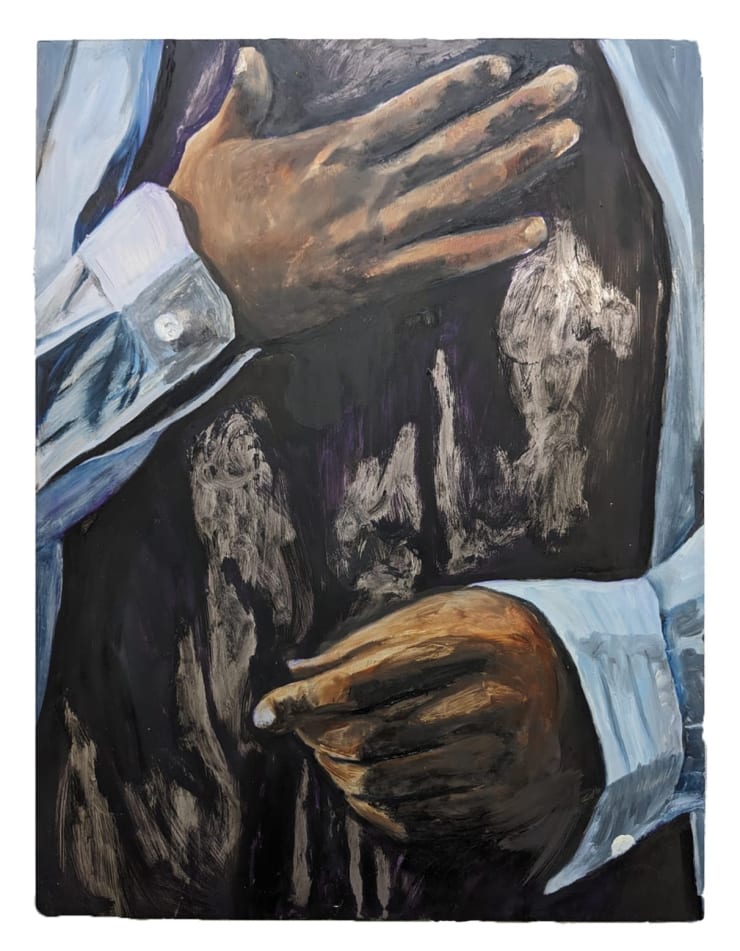

Bhasha Chakrabarti (b. 1991) is interested in exploring how artwork, even when grounded in local materials and symbols, can speak to issues beyond the local by situating her practice within global conversations around race, gender, and power.This pair of oil-painted tondos, along with the studies that accompany them, depict the hands of a past lover in moments of conversation, holding, and embrace. The titles of the works invoke the biblical text Song of Solomon (also known as the Song of Songs), which speaks of love through the language of touch, eroticism, and embodiment. In the Song, desire is known sensorially—through skin, gesture, and proximity—situating the body as a site of knowledge and devotion.These paintings underscore heartbreak as a bodily condition rather than a purely emotional one. Hands are rendered in isolation, becoming instruments of perception, care, labor, and survival, as well as vessels of memory that carry both tenderness and loss. The circular format suggests reciprocity, repetition, and return, mirroring how longing revisits the body over time. Touch becomes not only a private register of intimacy but a way of knowing the world, foregrounding the body’s capacity to remember even when contact has ceased. Echoing Audre Lorde’s call to “not let your head deny / your hands / any memory of what passes through them,” the paintings insist that the extremities of the body function as both instruments of knowledge and archives of feeling. Here, touch—historical, emotional, and embodied—remains a vital, sustaining force rather than something flighty or superficial.

-

-

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) I, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) I, 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) II, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) II, 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) III, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) III, 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) IV, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) IV, 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) V, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Just Your Hands (after the Song of Songs) V, 2025

-

-

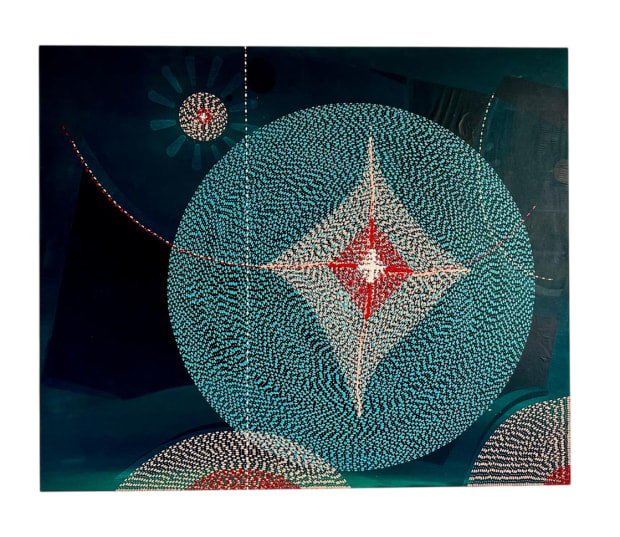

Praneet Soi’s (b. 1971; Kolkata, India) oscillatory movement between his artistic bases in Amsterdam and Kolkata impacts his practice. Soi identifies, over time, patterns that emerge from an investigation of his extended social and economic landscape and explores these across a multidisciplinary oeuvre. Ever since his first immersion in 2014 with the local craftsmen in Fayaz Jan’s Karkhana or studio, Soi has been returning to Srinagar to intertwine himself within the Karkhana’s working rhythm, making decisions with the craftsmen about the motifs, pertaining to their colour and composition, that are historically recognisable within the region’s craft industry, but which push away from their original decorative trajectory into what might be described as experimental compositions. Soi oftentimes introduces his own imagery into the conversation, opening up interesting possibilities to explore with craftsmen.Soi will be showing a new body of work that brings together his sustained engagement with the Kashmiri craftsman Fayaz Jan and, through this, his growing familiarity with the landscape of the Hasanabad area where Jan’s Karkhana is based. The Hasanabad Discs reflect this. The surfaces—built from papier-mâché, clay from the River Jhelum, chalk dust, and tissue paper sealed with saresh—create richly absorptive grounds for painting. The backgrounds are painted on by craftsmen, using floral motifs ubiquitous to the region. Soi asked them to reduce certain of the patterns to their basic elements, allowing them to become grounds over which he painted, en plein air, imagery from the Hasanabad region that had gradually become familiar to him over a decade of working there.In Hasan Abad: View of the Zabarwan Range, a radiating pattern inspired by the Mosaic of the House of Citharist of Pompeii, which Soi had come across in the Archaeological Museum in Naples, frames a silverpoint drawing of the Zabarwan mountain range visible from the craftsmen's karkhana.The ongoing series Landscape(s) underscores Soi’s elucidation of landscape as a construction of multiple viewpoints, stitching together his references drawn from personal experience and research, such as local Kashmiri architecture, Buddhist histories (Buddhism was a major religion in and around Srinagar, of which little trace remains), and Amsterdam’s Oosterpark, situated adjacent to Soi’s studio.Sculptural works like the Bird series and Two-headed Bird are studies in colour, pattern, and figuration simultaneously. They also mark the beginning of Soi’s work with Khatambandhi—a craft in which ceilings are panelled with wooden patterns. These sculptural works are inspired by the Modernists, such as K. G. Subramanyan, and the Arts and Crafts movement of 19th-century England in bridging myth with motif-making with pattern. In Indian mythology, the two-headed bird alludes to the Gandabherunda.In Spring (Avian Window), isolating the blocks that make patterns, Soi began to see how adding them together formed windows that were interesting. Bird-like forms appeared, similar to this work, tying patterns to figuration. Soi decided to use them as windows in which he could experiment with the artisans in making experimental compositions. These works extend his inquiry into pattern, figuration, and drawing from Khatambandhi ceilings and papier-mâché tiles to stitch disparate geographies into a shared visual language.

-

-

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View of the Zabarwan Range, 2025

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View of the Zabarwan Range, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: Creepers from Fayaz garden, 2025

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: Creepers from Fayaz garden, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: Canal Reflection, 2025

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: Canal Reflection, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View from across the canal part 2, 2025

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View from across the canal part 2, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View from across the canal part 1, 2025

Praneet Soi, Hasan Abad: View from across the canal part 1, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025

Praneet Soi, Bird, 2025 -

Praneet Soi, Landscape(s), 2025

Praneet Soi, Landscape(s), 2025

-

-

T. Vinoja’s (b. 1991; Kilinochchi, Sri Lanka) practice is influenced by contemporary art and Tamil literature, particularly the lived experiences of the Sri Lankan War (1983- 2009). Her work explores the war-torn landscapes, social conflict, and collective memory. Rooted in textile-based practices, her weaving embodies the concept of skin—both as a physical boundary and a metaphor for land, identity, and loss. The act of weaving itself is a process of connecting lines, much like the threads of history and personal experience. These lines symbolise both the fragility and resilience of human existence. Fabric, like skin, accompanies us through life and death, serving as a second layer that records our presence and absence. Through her practice, Vinoja seeks to evoke this enduring relationship between body, land, and memory, reflecting on the marks left by war and the stories woven into our collective past.

-

Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah (b. 1989, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka) is a multimedia artist whose practice ranges from installations to performance-based soundscapes, videos, and drawings. His work focuses on the destructive impact of Sri Lanka’s prolonged civil war, its effects on the ecological world and the lives of people existing amidst the ceaseless violence and trauma. Using motifs such as mycelium, reminiscent of the damaging wounds inflicted on nature, while reflecting on how land becomes the bearer of the vestiges of war, Pakkiyarajah’s work explores how nature is rendered vulnerable due to human actions and offers a lens into how they are inextricably linked to each other.

-

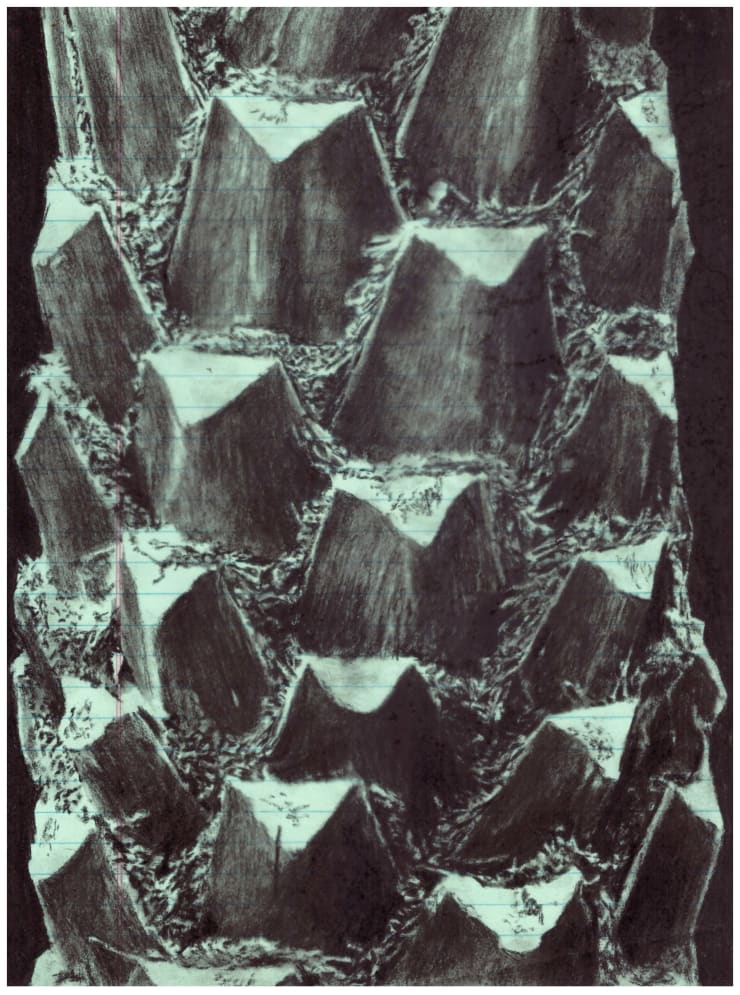

Prabhakar Pachpute (b. 1986; Sasti, Chandrapur, Maharashtra, India) works in an array of mediums and materials including drawing, light, stop- motion animations, sound, and sculptural forms. His use of charcoal has a direct connection to his subject matter and familial roots, coal mines and coal miners. Pachpute often creates immersive and dramatic environments in his site-specific works, using portraiture and landscape with surrealist tropes to critically tackle issues of mining labour and the effects of mining on the natural and human landscape. Using Maharashtra as a starting point, the artist combines research from around the world and personal experiences, moving from the personal to the global investigating a complexity of historical transformations on an economic, societal and environmental level.

-

-

Kallol Datta is a maker and researcher. Their practice reflects upon reconstructing, repurposing, and restructuring donated items of clothing and reclaimed textiles that hold memory, episodic events, and history, to negotiate larger questions about work and production, of labour and use, cultural sustainability, and of ideas revolving around research as production. The Dispatches series resides within the fifth chapter in Volume 4 - Misleading Truths Our Clothes Told Us. These dispatches are witnesses to episodic events in the Korean Peninsula during the early and mid-1900s and draw parallels to the social and bio-political ongoings in global societies today.

-

-

Soumya Sankar Bose (b. 1990) reconstructs archival materials and oral history into photography, films, alternative archives, and artist books. His hybrid mode of practice interweaving long-term research and engagement with local communities including his own family history accentuates certain subaltern experiences of the marginalised yet resilient in post-Partition Bengal.We Need to Talk in Whispers fits within the broader themes and concerns that permeate his other works. With the support of the Institute for Advanced Studies, Nantes, France, he has tried to build a narrative world that bridges the physical incidents and subjective emotions that accompany such experiences using references found in newspaper archives or court verdicts such as suicide notes, death announcements, social media posts, or the memories of those affected by the death of a loved one.

-

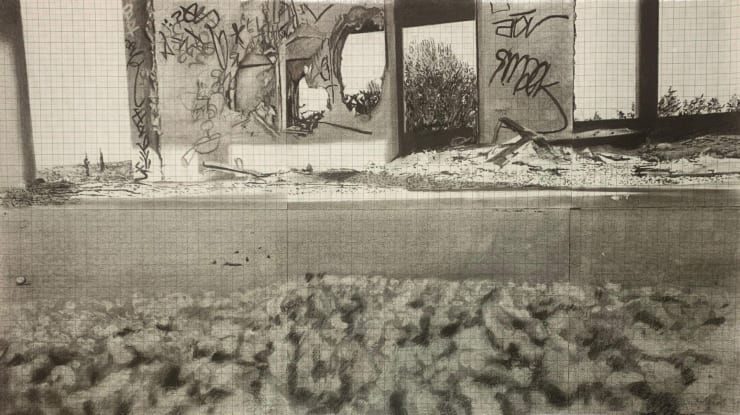

Julien Segard (b. 1980; Marseille, France) carefully considers the urban environment, the crevices where the constructed meets the natural, and how the two become inseparable. His works feature an assemblage of found elements and architectural structures that exist because of humans, but are bereft of human presence. The intimate, symbiotic, and oftentimes destructive relationship between man, nature and architecture become points of introspection for Segard in his works. Rooted in experiences of solitude and silence, Segard’s practice immerses the viewer in the minuteness of their elements while simultaneously operating as the entry points into vast infinite spaces.

-

-

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXI, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXI, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIV, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIV, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXV, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXV, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXX, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXX, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXVII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXVII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXVIII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXVIII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIX, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXIX, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XX, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XX, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXI, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXI, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXIII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXIII, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXV, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXV, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXIV, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXIV, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXVI, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXVI, 2025 -

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXVII, 2025

Julien Segard, Dialogues intérieurs à la périphérie XXXVII, 2025

-

-

At the centre of Vikrant Bhise’s (b.1984) practice lies the ubiquitous presence of casteism which is entrenched in the social, economic, and political rubric of the nation and its intersectional implications on the movement for land, liberty, and labour.This body of work extends his previous series, which focused on snake charmers, monkey charmers and street performers who move from village to village, living without a permanent homeland. These migrant communities set up temporary tents using whatever materials they were able to accumulate; these tents become their abodes and the only spaces they can call their ‘own’. Tents, in particular, carry layered political meanings. They can function as theatres for itinerant performers who wander from place to place, speaking to the lives of such communities, and they can also serve as shelters for worn-out bodies during moments of protest. The works reflect Bhise’s own mindscape, where land, tents, cloth, people, and other objects churn together in a constant state of turmoil—much like the lives of these communities themselves. The Buddha, as the ultimate form of peace and liberation, anchors this practice. Drawing from Buddhism, Bhise derives his visual vocabulary through its iconography and architecture. The Chattra spire—the crowning element of a stupa—emerges as a symbol of peace and protection, offering a form of hope for these people. The presence of Babasaheb Ambedkar serves as a reminder of his enduring call—“Educate. Agitate. Organise.”—which remains a crucial tool in the struggle against injustice and oppression.

-

-

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Grounds, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Grounds, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Denied Lands 1, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Denied Lands 1, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Denied Lands 2, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Denied Lands 2, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 1, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 1, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 2, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 2, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 3, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 3, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 4, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 4, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 5, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 5, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 6, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 6, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 7, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 7, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 8, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 8, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 9, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 9, 2026 -

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 10, 2026

Vikrant Bhise, Unsettled Lives 10, 2026

-

-

Rathin Barman’s (b. 1981, Tripura, India) examines the nuances of the modern built environment as a tool for understanding socio-political history. Barman often breaks down the thoroughly engineered and fixed construct of a ‘home’ into a graphical outline of formal abstraction. In the Spatial Distortion series, Barman explores the notion of a ‘home’ as a living organism, as the configuration of spaces and other architectural features morph over time to mirror the mutability wrought in the time and lives of people. Concurrently, Barman also explores the various nuances of fragility and materiality with regard to architecture. In common parlance one does not associate the notion of fragility with a material such as concrete, but Barman through his experiences of working with materials of construction emphasises how this material also demands delicate handling and would often require multiple interventions of repair, much like the structure of a house which also needs renovation and maintenance for it to endure the ravages of time. One often notices how Barman plays around with the assumed infallibility of permanence by choosing concrete as his medium, which is both porous and rigid at the same time. The Spatial Distortion series seem to highlight the certain shifting facets, maybe an addition of rooms, walls or extension of a balcony through the use of lines, colours and charcoal planes in multiple tonalities on pigmented concrete panels. The sculptures also evoke the past grandeur of these edifices, once based in the imposing colonial architecture, but have now succumbed to decay and ruin.

-

-

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 1, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 1, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 2, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 2, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 3, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 3, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 4, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 4, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 5, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 5, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 6, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 6, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 7, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 7, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 8, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 8, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 9, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 9, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 10, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 10, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 11, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 11, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 12, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 12, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 13, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 13, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 14, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 14, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 15, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 15, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 16, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 16, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 17, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 17, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 18, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 18, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 19, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 19, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 20, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 20, 2026 -

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 21, 2026

Rathin Barman, Spatial Distortion 21, 2026

-

-

For any further information and press related enquires please write to admin@experimenter.in

India Art Fair 2026

Current viewing_room