-

Experimenter presents a group exhibition with works by Ayesha Sultana, Aziz Hazara, Bani Abidi, Bhasha Chakrabarti, Biraaj Dodiya, Emily Jacir, Judith Blum Reddy, Julien Segard, Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah, Radhika Khimji, T. Vinoja, and Vikrant Bhise at Art Dubai 2025.

-

At the centre of Vikrant Bhise’s (b.1984; lives and works in Mumbai, India) practice lies the ubiquitous presence of casteism which is entrenched in the social, economic, and political rubric of the nation and its intersectional implications on the movement for land, liberty, and labour. His body of work Migrant Labour Unfolding documents the migration crisis brought forth by the COVID-19 pandemic. The 21-day national lockdown in India, which stalled transportation services, forced inter-state migrants to walk thousands of kilometres across borders to reach their homes. With state borders sealed and work coming to a halt, the migrant-labourers faced severe hardships, which were further aggravated by the dilution of labour laws as reforms. Bhise also draws inspiration from Laxman Mane’s autobiography Upara (Marathi for ‘outsider’) that explores the life of a migrant, focusing on themes of poverty, discrimination, and the struggle for social justice. The works underscore how the lived realities of the migrant communities haven’t changed much in the years that have followed. They encapsulate fear, flux, hunger, and survival not just as visual documentation of history but also to raise critical questions.

-

T. Vinoja’s (b. 1991) practice is influenced by contemporary art and Tamil literature, particularly the lived experiences of the Sri Lankan War (1983-2009). Her textile-based practice explores the war-torn landscapes, social conflict, and collective memory. Vinoja’s weaving embodies the concept of skin—both as a physical boundary and a metaphor for land, identity, and loss. The act of weaving itself is a process of connecting lines, much like the threads of history and personal experience. These lines symbolise both the fragility and resilience of human existence. Fabric, like skin, accompanies us through life and death, serving as a second layer that records our presence and absence. Through her practice, Vinoja seeks to evoke this enduring relationship between body, land, and memory, reflecting on the marks left by war and the stories woven into our collective past.

-

-

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025 -

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

Bani Abidi, Society for aching bodies, 2025

-

-

Bani Abidi

Society for aching bodies, 2025Bani Abidi (b. 1971; lives and works between Berlin and Karachi) reflects on the tremendous social ruptures as well as new forms of radical collectivity that have mushroomed around her since the start of the most recent iteration of the longstanding Israel-Palestine conflict. On 26 October 2023, Abidi hosted an impromptu gathering with old friends and new acquaintances, inviting them to bring with them “a text, a poem, a conversation… that can hold our hand through this time of grief and exhaustion.” Her first artistic response to this seismic moment was to look at these gatherings and conversations as kinds of secret testimonials. Over eight months, as the drawings evolved with the escalating dangers and subjugation of anti-genocide voices, so did the desire to hide the faces of all the people who gathered. Society for aching bodies is a set of drawings based on these gatherings that Abidi has hosted in her Berlin home in response to the heartbreaking social ruptures that have emerged in the wake of recent crises. The series underscores the power of small gestures of collective resistance anchoring us in hope and resilience. -

-

Bhasha Chakrabarti, High tide in Alang, 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, High tide in Alang, 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (cranes & watchmen), 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (cranes & watchmen), 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (chains), 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (chains), 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (birds & boundary walls), 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (birds & boundary walls), 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (dogs), 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (dogs), 2025 -

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (windows & doors), 2025

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard (windows & doors), 2025

-

-

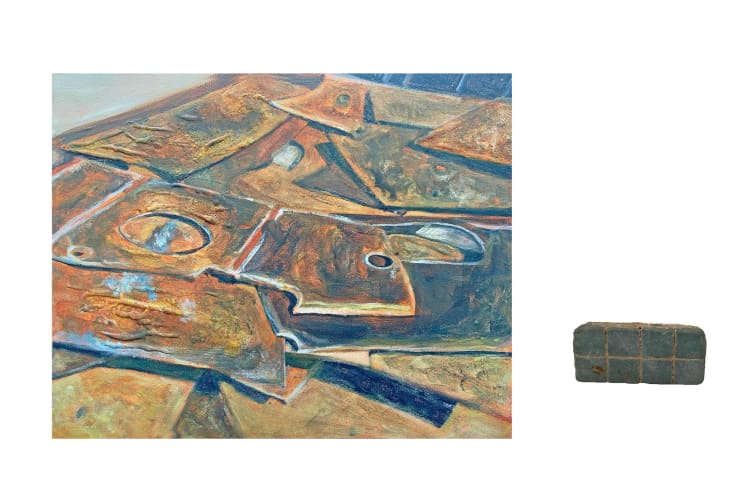

Bhasha Chakrabarti (b. 1991, Honolulu, HI; lives and works in New Haven, CT) is showing a new ongoing body of work titled The Ship as Co-Conspirator (to capitalism and to its undoing).

90% of the world’s commodities move by sea. The ships that do the moving are beasts. Their sheer scale likens them to untamable, inhuman creatures; but it is their traitorous nature, especially at the “end” of their lives that reinforces the beastliness. Despite being carefully forged, wielded, and tended to by global capitalism, these disloyal vessels refuse to go gentle into the good night after having served their time. Their bodies, capacious, and limber at sea, become leaden and unwieldy once beached. As they are painstakingly dismembered, their blood, guts, and bones rage against their masters; leaking, crashing, spilling, exploding, and violently exposing the truths of the system that fathered them.

In the Inside-Out series we are presented with 5 portholes from decommissioned ships, but rather than gazing out onto a land- or sea-scape through the windows, we see the ship’s innards. Teetering between abstraction and body horror, these oil paintings provide glimpses into the visceral particularities of a seemingly inert, container ship and reminds us to shift our gaze away from the horizon, and turn inwards to observe the health of the system and mechanics upon which our hasty navigation towards “growth” and “progress” is based.

More than 85% of all of the world’s ships are broken down on 3 beaches in South Asia: Alang in India, Gadani in Pakistan, and Chittagong in Bangladesh. Once broken, almost every part of the ship, from the engines and motors at its heart, to the steel, wood, fiber, and glass of its body, to the furniture and furnishings it is adorned with, is resold/reused/recycled. But, as with all industrial recycling processes, the work is dirty and dangerous. Although much of the ship does get recycled, the sands of these beaches are littered with plastic scraps, tile fragments, and occasional corpses of dogs, cats, and birds who have finally lost the daily battle against toxins like asbestos, fuels, and heavy metals which ooze out of the dying ships. The works in Notes from the Ship-Breaking Yard document daily life at the ship breaking yards—a saluting uniformed watchman, seagulls sitting atop a boundary wall constructed from ship parts, a dog, all four legs coated with a suspicious black muck, assessing your intentions on her section of the tile-littered beach. These quotidian scenes attest to both the possibilities and the limits of recycling. While much global criticism has centered on the labor practices and environmental impacts of these ship breaking yards, these works focus on the sheer impossibility of the task to begin. Do we, the consumers reliant on a globalized market, take enough responsibility for our part in perpetuating this vicious, inexorable, and inhumane system?

Based on time spent at the two the largest ship breaking yards in the world (directly referenced in the works High Tide in Alang and Low Tide in Chittagong), these works attempt to annotate the portrayals and betrayals of ships as they transition from carrier /container to deadweight cargo and waste. By not just depicting but also collecting and using the byproducts and debris of the ship breaking process as surface, pigment, and framing device, these works re-materialize neoliberal abstractions of “commodity flows” in order to highlight the decisive failure of the promises of “recycling” as a sufficient antidote to capitalist greed.

-

-

Ayesha Sultana’s (b. 1984; lives and works between Jashore, Bangladesh and Atlanta, USA) practice is an ongoing investigation of drawing, of seeing space in continuum, of exploring gaps in visual memory and of looking at the periphery and what is overlooked in plain sight. The act of mark-making and repetition is at the crucible of Sultana’s practice and these deliberations are revealed through the drawing series Breath Count. Emphasizing on awareness of her breath through scratching the surface of clay-coated paper are personal explorations of mark-making and corporeality for Sultana. They are a contemplation of the interconnectedness of her own body to larger systems. Cutting into the surface of the paper, Sultana reveals patterns that represent a delicate inward probe using time, rhythm, and removal in breath.

-

Julien Segard (b. 1980 in Marseille, France; lives and works in Goa, India) carefully considers the urban environment, crevices where the constructed meets the natural, and how the two become inseparable. His works feature an assemblage of found elements and architectural structures that exist because of humans but are bereft of their presence. The intimate, symbiotic, and oftentimes destructive relationship between man, nature, and architecture become points of introspection for Segard in his works. Rooted in experiences of solitude and silence, Segard's practice immerses the viewer in the minuteness of their elements while simultaneously operating as entry points into vast infinite spaces.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Art Dubai

Current viewing_room