-

ECH Day 6 Summary by Mario D'Souza

“I will do what I can and I will say what I should. These intolerant voices find strength in our silence. Let them learn to argue using words, instead of threats” - Gauri Lankesh.

The call to speak truth to power, hold it accountable and challenge its ideas with veracity - is the very foundation of Journalism. It must not be seen as courage, it exists as a duty to the people. To call it courage is to place it outside of the ordinary – and if that is the odd case then we must be worried, very worried.

Ayyub started her note by reminding the audience of the arrest of Samriddhi Sakunia and Swarna Jha’– two women journalists, who were covering the recent communal incidents in Tripura were arrested by Tripura police. “I wish to have given you an optimistic picture” but “it is an extremely frustrating time not (only) as a journalist but as a citizen of this country where we have long cherished our democracy and (ideals of) secularism” continued Ayyub. Unlike a lie or a rumour, the truth must persevere; be told over and over again, and work to find favour. Your “readers keep asking you why are you saying the same things again and again, you sound repetitive”. “Journalism is on a ventilator in India and my friends said that there are too many of us writing and speaking the truth, but we are not the mainstream media”. A majority of the Indian population, particularly those in rural areas are accessing Hindi news channels and subscribing to their propagated truths and ideologies. This seeds a very specific and dangerous condition – news agencies as makers of truth, instead of those that carry it. What happens to the process of veracity when those entrusted with it decide to produce ‘truths’ instead?

To speak the truth also comes at a price. Ayyub’s next book is titled The Beautiful Isolation – “never before have I felt so isolated not just as a journalist but as a human being who is losing friends every day” – friends who no longer want to be seen in public with her. “I am not here to be brave, not here to be courageous because that hurts.” Responding to Ginwala’s question about informal networks and learnings that emerge from being in conversation with journalists in similar conditions such as ours, Ayyub spoke about Maria Ressa, and the assassinated Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia – and the threat that binds each one of them and their families. Oppressive regimes across the world have positioned journalists as the enemies of the state. “How do you attack them? If it’s a man you abuse him, charge him of collusion, corruption, national security and if it’s a woman you intimate them online, book for treason”.

One of the reasons she chose to be at the Curators’ Hub “is to feel a sense of empathy and that I am not alone and that there are people who are listening to me right now and that people are still believing that there will be a day when the India of our dreams will be realized.” In the course of her address Ayyub left us with two thoughts. The first is that “bigotry is all pervasive and this belief that oh it’s not going to come to us…hate cannot be confined. When you unleash the demon called hate it will not just come to my door but come to yours too.” The second was that she is not going to speak for any of us – “you have to fight this battle yourself…this is my personal battle and I am fighting for the idea of India that I believe in, I am not fighting it on your behalf”.

It was a difficult transition to the group discussion - where we were joined by most presenting curators of this edition – difficult not only because of what Rana said, but also because it cut right through our individual and collective silences.

Osei Bonsu reflecting on “how we could be together post-pandemic” asked Ginwala what it would mean to conceptualise and organise a forum such as the hub. To which she reminded us of the “shrinking public sphere” and “what does it mean to gather in this way” in a space that not only asks you to discuss propositions, but failures. She placed her faith in “listening to people”, which may enable debates and a recognition of features and strategies amongst us.

Ginwala addressed the ideas and aspects of representation that are being widely used at this moment particularly in institutional politics and positioning. In this “rhetoric of diversity” and the “co-option of critical practice by institutions at the center of the internationalised art world, how can we in our work represent an ethics of diversity (after Kwame Anthony Appiah) to allow for forms of difference to continually be generated? Bonsu replied by foregrounding how calls for diversification of arts on face value can be detrimental to its possibility. There is a need to shift methodology in a critical way. Inviting diversity into structures and modes of knowledge that were essentially imperial and colonial - is “violent and inhospitable” in many ways. He suggested that this repair needs to happen in silence at and internally because of the lives entangled within them and from lived experiences. Johal reminded us that despite all of the machinery of the institution - the encounter of the visitor with the artwork is something we can and should hold onto, “it has charge and power and meaning”.

Responding to a question about experimental pedagogic models that are created as efforts of decentering - that are forged and formed from conditions on the ground - and how does one continue the process also in the framework of ethics of diversity, Aline Khoury foregrounded how Palestinian communities have always been diverse. She also expressed her fears as well, with the settler-colonial occupation disrupting these harmonious relationships in its bid to destroy these ways of life. Diversity takes a different meaning and form at Dar Jacir and emerges from intimate forms learning and sharing.

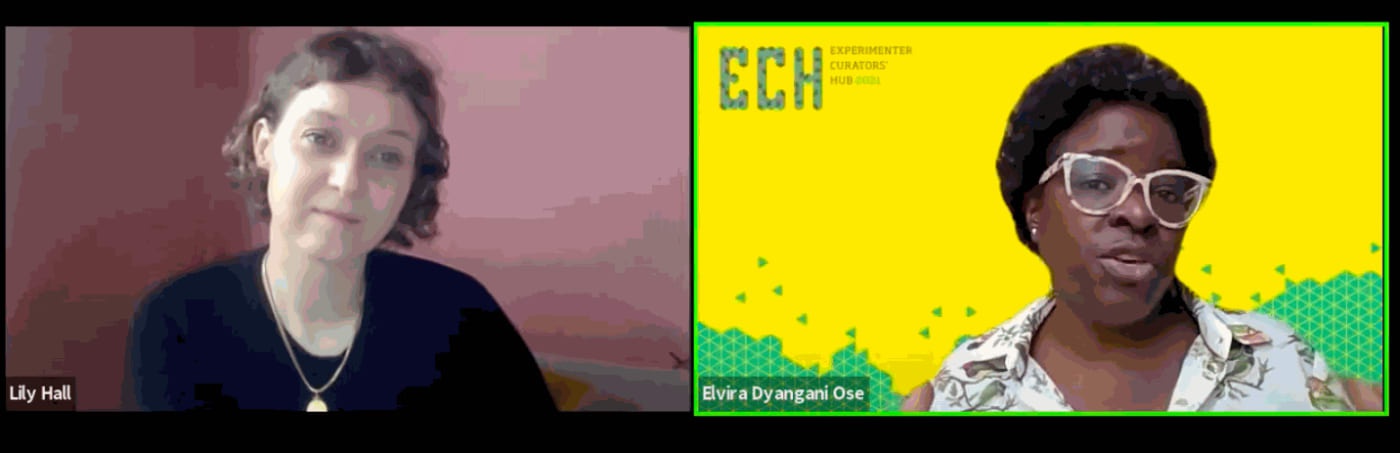

Lily Hall also pointed out that a lot of these structures are held into place by the need to fit certain mandates that enable governmental and other modes of funding. Bonsu continued to extend from Elvira Dyangani Ose and Hall’s conversation from the previous day to further note the “transfer of knowledge” as a generative mode. “Ethics of diversity has got to do with listening as we’ve heard from Rana” but also listening “deeply enough so that we can build a sense of commonality”. This goes beyond merely occupying our professional roles - to want to learn from someone for reasons such as the continuation of knowledge.

Finally I leave you with two things to think of and think from. The first is a question that Ginwala asked during the discussion: “How can we cede power to the communities we serve while maintaining the work central to our mission?”

And the second is this piece of poetry from Etel Adnan, who left us last week.

She also leaves with us, with the inheritance of her immense hope:

I am not at the mercy of men

since trees live in my fantasies

men and trees long for fire

and call for the rain

I love rains which carry desires

To oceans.

-

ECH Day 5 Summary by Mario D'Souza

The acclaimed African writer Bessie Head is mentioned early on in Lily Hall’s presentation as she introduced us to an exhibition titled Women on Aeroplanes at the Showroom, where she is curator. Bessie exiled herself to Botswana on a one-way ticket with her son, following her experiences with Apartheid in South Africa. “I once sat down on a bench at Cape Town railway station where the notice "Whites Only" was obscured. A few moments later a white man approached and shouted: 'Get off!' It never occurred to him that he was achieving the opposite of his dreams of superiority and had become a living object of contempt, that human beings, when they are human, dare not conduct themselves in such ways.” wrote Head later.

Hall’s mention of Head was from a mural by Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum commissioned for the Showroom’s facade. Titled Exalt B.H. Sunstrum’s mural envelopes the building with Serowe’s landscape under the weight of the vast sky. Head’s words from Earth and Everything are etched over it. It reads “to the sky, to the sky, to the sky” on the left; “to the stars, to the stars, to the stars” on the right and then these two facades intersect by a single phrase “up these with me” Hall elaborated.

The fifth day of Experimenter Curators’ Hub hosted a conversation between Elvira Dyangani Ose, now Director of MACBA, Barcelona and former Director of the Showroom in London and Lily Hall, her former colleague and currently curator at The Showroom. To give us a sense of where the Showroom conceptually and structurally stands at this point, Hall informed how she along with her colleagues are “thinking ahead and imagining alternatives” for the present and future of the institution. “For me and our team, we come with the inclination and a real necessity to return to the material realities and conditions on the ground, the here and the now from within which we imagine. “This relay of productive tension between the imaginary and the material conditions from which and with which we enact those imagined possibilities in practice and everyday life is something that we consider and work through in all of our collaborations”.

The Showroom is planning long term - “to present new challenges that we face within and beyond this current situation”. A question they are asking is: How does a small scale institution embody the values that we share and enact those on a daily basis, when delivering in quite precarious conditions? “It feels like a very generative moment to take stock and have the capacity to open up to alternative modes of instituting”. To start by also asking “Who has a stake in that very decision making process? What are the visible or less visible power structures embedded and in play in our current status quo?”

Dyangani Ose continued to ask: “How can we support each other and build a sense of new institutional model from there and discuss the possibilities that the exhibition has to afford to the institution - intervene with the institution?” She noted how her work with the Showroom has allowed her to think about “how can (we) develop strategies that are used around issues of identity and create a sense of belonging to certain stories, agents and narratives to a space given to (us)? How can I intervene from these positions of post colonial subjects as a descendents into the official now?”

“It has to do with what frames us in the first place” she noted before responding to Ginwals’s prompts about generosity, about the black anthropocene[1], about the possibility of us intervening into the history of earth in a way that wasn't all white extracavitism. Dyangani Ose offers Carrie Mae Weems’ Framed by Modernism (1996) as a critical moment of disruption - the first presentation of an image of a Black man in the US presentation at the Venice Biennale. It broke “the canonical imagination of institutional history of the US representation in the biennale and (was) also equally still framed by all these conditions that had to do with how the modern art was captured by our imaginary” Dyangani Ose noted.

In the ensuing conversations stemming from a range of terms including care and Icebergian economies of contemporary art[2], Dyangani Osei spoke of the agency of the stakeholder and “how to formulate ways in which the most poetic ways of the institution connects with the most prosaic way” while flagging a sense in which “sometimes these visions go parallel with the possibilities of an institution” and enhance changes. Another question by Ginwala probed the lateral, invisible roots of a nimble-footed, agile institution as the Showroom and what it meant for Dyangani Ose and Hall to run it at a moment of political upheavals and economic breakdowns including Brexit, housing burdens, funding cuts etc. Responding to Ginwala’ “to arrive at the institution at a time of turmoil”, Hall referenced a programme titled This is no longer that place that directly attended to ideas of migration, displacement, security and access at the cusp of brexit. Hall reminded us of the power and need to create a space for dialogue where disagreements and other positions could be held, hosted. “It allows us to move somewhere together” - even if it was in dissonance.

Nodding to Priyanka Raja’s opening remark about the need to come together at this moment and to orient the hub as a space to pose questions and share, Elvira reaffirmed the possibility of participatory models of thinking and making - like at the Showroom or at the MACBA and also at the Curators’ Hub. “The idea of generosity has its own power” and proposed affection as a subversive strategy of an institution, extending and expanding far beyond the idea of care.

[1] After Kathryn Yusoff https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/a-billion-black-anthropocenes-or-none

[2] After Kathrin Böhm and Kuba Szreder

-

ECH Day 4 Summary by Mario D'Souza

Palestinian scholar Sanabel Abdel Rahman writes about the Arabic word istimāta.

“Istimāta” means to do every single thing physically and metaphysically possible towards something; to such an extent that death, “al-mawt”, becomes as acceptable as life itself. Arabs and all the colonized peoples have been enduring a lifelong “istimāta” towards hope. A collective ‘istamāta” to topple their regimes, liberate their lands and stop a 73-year-old and ongoing ethnic cleansing that the world has just become aware of.

Through the conceptual, philosophical and structural modes of home and family, on the fourth day of the Experimenter Curators’ Hub, we returned to hospitality and hope under hostility. One, that is colonized and under constant distress from various actions including forceful occupation, ethnic cleansing, extraction and historic-cultural erasure. Independent curator Rattanamol Singh Johal invited Emily Jacir and Aline Khoury from the Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research, a grass-roots independent artist–run initiative founded in 2014 in Jacir’s family home Bethlehem.

In her introductory remarks Natasha Ginwala quoted James Baldwin -“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition.” The violent, physical act of forceful occupation and displacement of the Palestinian people perhaps heightens this irrevocable condition in the loss of the tangibile." The perimeters of my house are all that are left of Palestine" – writes Palestinian lawyer and writer Raja Shehadeh in his heartbreaking diary When the Bulbul Stopped Singing.

The street where the Dar Jacir house lies is the historic Bethlehem-Hebron Road and has always been a conduit for movement and connection. Jacir noted “It is important to situate not only where are temporally and spatially, (but that) we are not in a postcolonial situation. We are living under a colonial apartheid. (This) needs to be clear because it frames our site and how we operate.”

As the presentation slides reached the Urban farm at the center, Johal prefaced the constant conditions emerging from colonial apartheid and its violent means and ways. Dar Jacir was raided and damaged by Israeli forces some months ago.; their urban farm destroyed and equipment stolen[1]. Even with the kind of heaviness this persistent condition brings to the space and its work – “How to find openings and the strength to re-group...and to find the joy of working with artists, collaborators and the community?”. Jacir responded by reminding us of the spirit of the space, one that is informed by a sense of hospitality, linking it to the early mention of structures and possibilities of family-building and co-sharing. Speaking about a workshop led by Michael Rakowitz at a time when they were not allowed into their own building due to renovations; Jacir narrated how they congregated in other and open spaces - the houses of neighbors, the street, refugee camps, bars, supermarket – a kind of temporary hospitality and the neighborhood as an extended family.

Amongst other projects that essay this spirit of care, conservation and community-building is artist Vivian Sansour’s Home landscape residency and workshop. Titled living seed library and the duality of stones it stemmed from the belief that architectural conservation cannot be complete without the botanical revival… preservation of the crops and plants that our ancestors developed, cultivated and propagated for our survival” noted Khoury. Sansour, who founded the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library close to Bethlehem, developed the Urban farm at Dar Jacir clearing the ground of glass and shrapnel and composting the soil, raising the beds and planting the land. Her workshop titled Home emerged from the heart-breaking incident of a mother who lost her son in the clashes. “He was hungry and when we found him, he had a bag of chips in his pocket. He was coming home for lunch” narrated Khoury.

Johal referenced Dar Jacir’s mission statement and prefaced its intention of reactivating ties and other kind of transnational networks across the Mediterranean while probing the conditions of the fragmentation and alienation of Palestinian communities from each other - by design and through violence. Jacir responded by reminding the audience that the Mediterranean region is one of shared histories – “of exchanges and traces on both sides of the shore, every side of the shore”.

Amongst other questions that emerged from the discussion were the effects of Covid on the work and programming of Dar Jacir. Khoury’s simple, sharp response reminded us of the mundaneness of violence, conflict and interruptions in the lives of the many who live under occupation and settler-colonial oppressive systems. “Except the lockdown, the conditions are the same” she noted, “the pandemic was just another obstacle in our lifeline” and how over the years they have learnt to find other ways of being together.

Johal returned to Dar Jacir as a space that is artist-led and women-led, also understanding the structures of funding. Several artists have over the years self-funded their participation as Dar Jacir which is one kind of support he reminded. Khoury noted how most of the funding comes with conditions of “what we should do” – “they are informing what the culture sphere should look like” according to their development ideals and agendas. In responding to the functioning of the space Jacir said “We talk about every aspect of what we are doing” nodding to Ginwala and Johal’s mentions of the scaffolding – “a scaffolding being movable – that the scaffolding itself is an infrastructure – also connotes something in process”.

In responding to Ginwala, Johal and the audiences about how re-invigoration of a destroyed soil is very much a part of Dar Jacir’s imagination – the idea of this green space is because there is no green space in Bethlehem for people to eat, grow, learn, live together noted Emily and thus the opening of and opening out of Dar Jacir and its spaces was key.

I conclude this text with two thoughts for you to carry away. The first is the image of the Urban Farm Workshop conducted by Mohammad Saleh where children had the change to prepare the soil, experience land and plant seeds – a history and inheritance they have deliberately deprived of by the settler-colonial Israel in a bid to erase Palestinian culture and its ways of life. The second is something that Aline Khoury said and it will continue to stay with me for a long time – “the Palestinians as a people have always been so connected to land – the seasons, the harvest , our rituals – everything is around our land.” Remember!

-

ECH Day 3 Summary by Mario D'Souza

The dear, departed Bisi Silva noted, “for me the local is extremely vast and maybe another way of talking about the global - because within the global there is a local and in the local of course there is a global. I am however very concerned about location, about specificity – I emphasise the local as a multitude”. A multitude of layers and conditions – historical, political, migratory and those still evolving. This observation came from Silva’s location and work in Lagos. This rootedness in location and its translation into many global registers and conversations formed one of the many surfaces that hosted the conversations on Day 3 of Experimenter Curators’ Hub.

In A Song for the Lagoon, Akeem Lasisi writes:

In this city of a thousand rivers,

The Lagoon looms like a sky lying upon its back

Queen of Lagos waters,

She wraps the city in an glittering lace

Neither does she depend on the rain-god,

Nor is she threatened by gluttons or drought

Eras and errors have passed away

But the Lagoon still flaunts the depth of the Lagos grace

Lasisi’s poem inspired the title for the path-breaking second edition of the Lagos Biennale - ‘How To Build A Lagoon With Just A Bottle Of Wine?’ – which Ndidi Dike’s A History of a City in a Box (2019) was first conceived for. Invited as a collaborator by Tate Modern’s Curator of International Art Osei Bonsu, the Lagos based British-Nigerian artist’s work formed a scaffolding to hold her complex practice, enmeshed in a multitude of local and regional histories. Bonsu, who was instrumental in the acquisition of this work for Tate, continued to unpack this global-local history, posing both provocations and extensions. The work itself included old wooden file boxes recovered by the artist to form a city-like arrangement of blocks. Some files reveal governmental receipts and documents from the 1980s, along with postcards, clippings and photographs. At the start of the conversation Dike read, “Information is one of the greatest currencies in Lagos. Information is hidden and buried. It is un-accessible to the people, and only permitted to those in power.”

In her opening remarks, Natasha Ginwala invoked the concept of Lateral Universalism responding to which Bonsu said “Lateral Universalism is key to the way we think about our practices in the art world as connected by continuous labour, and the way in which we are constantly building history on incestual memory, on the same ways of thinking in a circular motion, that will allow us to learn from each other’s work”. He further went on to unpack these thoughts with Dike’s practice and its relationship to those that came before as well as her intergenerational peers in the region.

Bonsu, who was previously an independent curator working closely with artists and diverse sites, flagged how working at the Tate has led to thinking about layers - of collection, exhibitions, display, and how you can bring a curatorial practice within that infrastructure. In his position he has been thinking about – “How African artists can play a role in re-narrating the stories that we tell (through museums, perhaps). Okwui Enwezor believed in the necessity of the institution as a space to act and to think historically in the present” he noted. “How can we treat the museum as a space for historical intervention and activation? How do we make sure that institutions do not become passive observers to history and preservers of history (belonging to) a set group of society, but become engaged through a pluralistic logic of history making?”

Through Dike’s work the conversation attempted to stage the contemporary as a portal for people to enter regional, local histories. “Taking a history and re-narrating it in powerful and instructive ways” – like Dike, Abdoulaye Konate and William Kentridge amongst others.

Amongst a relay of questions between Bonsu, Dike, Ginwala and the audience, was a reference to the political conditions of our countries ( the N-SARS protests and now the covid crisis in Nigeria for example) and how does the art community deal with it. Dike, with alarming simplicity, reminded us of our local and the larger realities of the majoritarian (aka third) world – “Artists have learnt to practice and produce work with the most minimum of resources”. She later adds “Your very existence is determined and fed by the political circumstances you are living with at that point of time - you just need to find a way to talk about it”.

In response to a question about the immense work done by the diaspora – in situating and teleporting the local in the cities of the global north, Bonsu reminded the gathering of a generation of African artists that worked in the 1960s, in the diaspora and were acutely invested in the cultural politics of post-independence nation-states in Africa. They believed in the possibilities of pan-Africanism and set a model for cultural exchange that we continue to reclaim in artistic and curatorial practices/movements. As curators we must be interested in the “politics of remapping and redrawing the future but also in how artists change the route/modes and interrupt our thinking”. He further spoke of his own part British, part Ghanian ancestry and noted how “we as curators take our biographies into our work - not just our intellectual biographies but also where we choose to live, where we are able to live, what visas do we get.”

An audience question (redirected to Ginwala by Bonsu) probed how curators from the majoritarian world are able to work in (or navigate) an institution that was originally designed to exclude us? “It has been a process of working across the hemisphere” she noted. To be both an insider and an outsider in the European model and to learn to configure beyond the official roles and designated work. Like Dike and Bonsu, she reiterated how we must put ourselves out there for artists who work against the grain, against all odds and against structures. For it is their courage that makes our work and institutions possible.

I saved a paragraph from Lasisi’s poem:

Then those who want our ports to run dry,

Must first wait for the ocean to dry

Let them await the death of the wondrous sea

Those who dream recession for our aquatic land.

-

ECH Day 2 Summary by Mario D'Souza

Emily Dickinson never left her house. She suffered from the ‘fear of open spaces’ (the world, rather). Yet from the security (or confines) of her room, she wrote a thing about hope for the world:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all –

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

The second day of Experimenter Curators’ Hub continued to hope for unusual communities, casual networks, radical hospitality and hopeful actions. Hospitality “as an unwelcome interruption, beyond a planned moment or association and thinking of it as excess where the language of participation may even be ways of making together”, suggested Natasha Ginwala in her opening remarks. In many ways the ensuing conversations enmeshed and departed from the institutional, bureaucratic and policy frameworks, we addressed on Day 1 with Stephanie Rosenthal and Grace Ndiritu. It differed in its approach though – Mikala Tai, Head of Visual Arts at Australia Council and Marc Goldenfein, co-founder of ArtsPay – responded to frustrations with action-based solutions and adaptive models.

Earlier on, Ginwala invoked the image of Simon Kofe, the foreign minister of Tuvalu who recently delivered his address at the COP26 UN climate summit standing knee-deep in the waters of the rising ocean. “We are sinking” he informed {1}. Tai responded to this invocation by suggesting the need to create images that intersect at the right moment to make an impact. Tai, former Director of the ambitious, pioneering small institution 4A Center for Contemporary Asian Art{2}, recently moved to this bureaucratic, and policy position, carrying with her a deep understanding of artists’ needs, their friendships and trust. She flagged her frustrations with the rigidity of governmental and private philanthropic funding models and stressed on the need to fill the “gaps” in support towards arts and arts institutions. In one slide she placed the “limitations of curating” and “opportunity of curatorial thinking,” one after the other to perhaps suggest how one neutralizes the possibility and ambition of the other.

Whilst the pandemic made us aware of our precarious lives, it also exposed the deep inequalities in our situated worlds. The past eighteen months imbued us with the need and hope for change. Charged calls for accountability and actions – in light of the Me Too, Black Lives Matters, unfair salary models and funding from settler-colonial, big pharma and the arms lobby amongst others – were made. But the ‘Art World’ went back to being its usual, passive (hopeless) self. The infrastructures continue to fail artists while pressuring them to consistently produce and oil the larger systems – organizations have been defunded or have closed down; the lockdowns have made their incomes increasingly unstable and there has been an extensive loss of jobs and opportunities.

Art reaches only that many audiences. Tai remarked how she moved away from “Art can change the world” to how it can make us debate, re-think (and if I may add) unlearn. “Art can put pressure on power”. Infrastructure though is another beast; the funding comes from sources outside our control – how can we challenge that?

How can we take control of the future then, Tai asked – the future we want as our legacy. How do you respect what’s come before while also building new futures? I add to this Ginwala’s “How to attend to emergent realities?” The answer in many ways was in the promise of substructures like ArtsPay. Goldenfein’s ArtsPay, that he co founded with Lara Thoms and Alistair Webster is a fintech{3} app, where every purchase contributes a processing fee towards artists. Simply put, the ‘general public’ supports the arts ecosystem by turning into consequential patrons. The money is led into a foundation that will dole our funds to artists and arts organisations. A model where patronage is not a task or a privilege, but emerges as a way of life.

Tai and Goldenfein posed questions to each other and invited the audiences to contribute to their understanding of global challenges, invisible models and other modes like ArtsPay that may (or could possibly exist) in our regional contexts. What are the gaps in the current arts funding landscape? Goldenfien asked Tai. “Knowing that grants exist, knowing that you can apply, to believe that you can apply”. An audience member further questioned accessibility, and disparate or meagre funding for traditional arts and crafts when compared to modern and contemporary practices. ArtsPay is currently working on a report that includes suggestions from artists across the spectrum to understand challenges and mitigate them in the Australian context. Responding to accessibility Marc suggested “no application grants” or creating ecologies where we “trust artists” easily as solutions.

Another audience question reminded the presenters and us of our shared realities and political states - Will platforms such as ArtsPay give right wing governments a further excuse to reduce arts funding? While we must continue to think about how we will avoid this co-option, Tai reminded us that artists have always been exposed to the risks and whims of governments and their changing agendas.

Funding for artists and emerging artist spaces and institutions is key to their confidence and development. It validates the work that they do whilst also enabling it materially. A good funding model then is one that allows artist to focus on their ideas and craft, whilst relieving them of the pressures of immediate sustenance and bills. Tai left us to think about “how do you create something that enables artists to recognize the moment themselves – this is the point I need to try and apply for this?” Perhaps the answer is in something Marc noted about ArtsPay – that its vocation is not to be a tool, but to be a structure that's going to give back to the ecosystem – an ecology of co-nourishment.

As Dickinson writes, hope is generous and only giving! It takes nothing of us to hope.

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me

{3} Financial technology (Fintech) is used to describe new tech that seeks to improve and automate the delivery and use of financial services through tech solutions.

-

ECH Day 1 Summary by Mario D'Souza

In 1977, Roland Barthes taught a course of lectures at the Collège de France thinking about human relationships, its forms and social models. Here is where idiorrhythmie — “a form of living together which does not exclude individual freedom” was conceived[1]” In Barthes’ living together, one recognizes and respects the individual rhythms of the other, where the social is inseparable from the ethical and perhaps the transformative. In many ways I read these impulses in the 11th edition of the Experimenter Curators’ Hub. Prateek Raja in his opening remarks posits - “How can we be equivocal about issues that confront us, underscore the differences that are inherent in it and yet build a constructive sustainable dialogue?”

Held online for the second year in light of the pandemic and ongoing global restrictions, the 11th edition of the Experimenter Curators’ Hub experiments with its very form. Introduced by Priyanka Raja, the format invited five curators, who in turn invited five collaborators including individuals and institutions. Conceptually, it also moves away from looking at past projects and instead thinks of the possible, the propositional.

In her introductory reflections, Natasha Ginwala invokes two critical voices. The first of the dear, departed Lauren Berlant who as Ginwala notes, “encourages us as affective subjects to continually calibrate our belonging to our (known) world and to strangers, to dream with eyes wide open while surrendering to vulnerability”. And to the poet Ellen Bass who writes in The Thing Is:

when grief weights you like your own flesh

only more of it, an obesity of grief,

you think, How can a body withstand this?

These two registers, one of our relationship to the world and strangers, and the second of the body’s to grief (one that we have come to experience immeasurably in these past 18 months since the covid-19 pandemic) coursed through the opening conversation between Stephanie Rosenthal, Director of the Gropius Bau in Berlin and her collaborator, the British-Kenyan artist Grace Ndiritu.

Grace read, “If you visit the Ancient Egyptian galleries at the British Museum in London on any given day, you may not realise that the objects on display are unhappy. They no longer feel special, but objectified – in the true sense of the word – because of the cultural and energetic violation that has been enacted upon them through being exposed to endless photographs of tourists and other museum visitors. These objects were never meant to be seen by a single ray of sunlight or looked at by millions of keen Museumgoers. Hence, they feel like they are being robbed of their agency, with no rights of their own. As such, they want to be free.[2]” Through this entry-point, Ndiritu led us into a meditative awareness – first of the body and then - slowly helping us contemplate the future led by an imagination of our youngest offspring inhabiting it.

Rosenthal followed by introducing us to her work with seminal performance and installation artist Allan Kaprow who resisted institutions and famously noted, ‘The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible.’ In Kaprow’s, ‘18 Happenings in 6 parts’[3], 1959, an evening of seemingly random but carefully choreographed activities were staged. They required the participation of both the audience and the performers to complete the piece. This interdependence, co-learning and habitation has in many ways informed the methodologies she has experimented with at the museum with her colleagues. Be it new modes of welcoming and hospitality with Otobong Nkanga or the Wanwu Council with Zheng Bo. Rosenthal later suggested that the institutions need to be recalibrated to become actants, so that like Kaprow’s intention with his work, something ‘new’ can be birthed each time over.

The conversation also consistently returned to the structural framework of the museum and its rigid, (sometimes violent) limitations. Ndiritu asked what is so wrong with our institutions that it needs external pressures (and protests if I may add) to enact modes of repair, inclusivity, accountable representation and change. Rosenthal cited the conservative structures perpetrated by decades-old rigid modes of ‘caring for art objects’, and the bureaucratic and administrative challenges with respect to funding and policies. She suggested and I quote, “It is a constant transformation that needs a constant rolling over. We are in a time where change is very likely”. A cruel optimism perhaps?

To an audience question on what is the one thing she would change in the Gropius Bau, Rosenthal offered the possibilities of organic, fluid, adaptive structures – to incubate and let something grow as it comes along instead of the expectation of planning something to the very end. Perhaps this is an impulse the hub also adapts this year, as do we all, particularly in the light of the political upheavals, social shifts, calls for accountability and recuperation; as well as the vulnerabilities aggravated by this time of contagion. A note that I believe will linger on the ensuing conversations in the coming days.

[1] Barthes refers to the history of oriental monasteries, their rules and social relationships. Barthes also uses the fiction by Thomas Mann, André Gide, Émile Zola, Daniel Defoe, and often refers to Proust to further illustrate these ideas.

[3] Allan Kaprow: 18 Happenings in 6 Parts - 9/10/11 November 2006 (Hardback). Steidl Publishers, with

Allan Kaprow (artist), Stephanie Rosenthal, Eva Meyer-Hermann and Andre Lepecki.

-

Dr. Stephanie Rosenthal

-

Grace Ndiritu

-

Mikala Tai

-

Marc Goldenfein

-

Rattanamol Singh Johal

-

Emily Jacir and Aline Khoury, Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research, Bethlehem.

-

Osei Bonsu

-

Experimenter Curators' Hub, 2019.